© Photo: Dr. Graham's Homes / TCC Photo Archive

This paper attempts to highlight the spatial significance enjoyed by Rhenock as the first halting station along the old silk route via Jelep-la in Sikkim until 1962 and the subsequent emergence of small-scale businesses mostly run by the Newari businessmen – connecting the peripheral society into the system of the ‘modern world’.

Assam, North-East India served as the major trade hub along the Southern Silk Route. Traders from all over Europe and the neighbouring South Asian countries like Nepal and Bhutan passed through Assam before making their onward journey to Tibet via Myanmar. But there also existed an alternate trade route to Lhasa (Tibet) that passed through Jelep-La in Sikkim via Kalimpong in West Bengal also known as the Old Silk Route.

Trade networks have played a pivotal role in the making of societies by connecting distant places and serving as a conduit for the exchange of goods and the spread of knowledge, ideas and culture. One of the largest and predominant trade networks that connected China and the Mediterranean through land and maritime routes was the Silk Route significantly known for the trade of silk and spices across continents. The vast network of trade activities also witnessed the influence and development of science, culture, and art along the ancient Silk Route. However, a much lesser-known ancient Silk Route that connected Asia, Europe, and Africa was the Southern Silk Route that passed through the North-East part of India via Myanmar to Tibet. This trade route enhanced the already established economic and cultural interaction/exchanges between East Asia and the rest of the world.

© Photo: Dr. Graham's Homes / TCC Photo Archive

Assam, North-East India served as the major trade hub along the Southern Silk Route. Traders from all over Europe and the neighbouring South Asian countries like Nepal and Bhutan passed through Assam before making their onward journey to Tibet via Myanmar. But there also existed an alternate trade route to Lhasa (Tibet) that passed through Jelep-La in Sikkim via Kalimpong in West Bengal also known as the Old Silk Route. This trade route was shorter than other routes to Tibet via Kashmir or Assam which covered a distance of 2000 miles while the distance between Kalimpong to Phari, a station close to Lhasa, was just 95 miles (Majumdar, 1994). Furthermore, it was 12 miles shorter and cheaper to construct and maintain the Jelep-la route compared to another route to Lhasa via Nathu-la in Sikkim.

The more suitable climatic conditions and, an easy gradient provided better mobility for the traders and the mules. The Lhasa-Kalimpong trade route via Jelep-la became more popular after the British expedition led by Francis Younghusband to Tibet via Sikkim in 1903-04. The expedition was initiated to ‘resolve’ territorial dispute between Sikkim and Tibet and further ‘open up’ commercial and diplomatic relations with Tibet - (Mckay, 2012) Sikkim at that time was a protectorate of British India.

Photo: Praveen Chettri

The imagery of the Silk Route being witness to traders in a caravan travelling across continents for the exchange of the richness of silk and the warmth of the wool, an array of spices, shiny precious stones, and the aroma of flavoured tea along with the spread of art and culture is a rather romantic one! The romanticism of the old silk route that still lingers today was, however, far from reality with traders journeying over the arduous and treacherous mountains, in stages, depending on the weather conditions and the health of the traders and the mules. The journey necessitated halting stations – halting stations that go almost unnoticed amidst the credits given to major trading hubs for the exchange of goods, culture, ideas, and the development of international relations.

Rhenock, a small village in East Sikkim served as the first halting station in Sikkim along the Lhasa-Kalimpong trade route. It was also much closer to Kalimpong, one of the major trading hubs, than Gangtok which connected Kalimpong and Lhasa via Nathu-la. Rhenock, also known as the Black Hill in the Lepcha language; Rhe meaning Black and Nock meaning Hill, got its name from the rampant malaria that plagued the village, as well as the frequent fire that razed the village down. More importantly, the name Rhenock is a memory that echoes of a past where traders from all over the world along with their Khacchars (mules) and heavy goods camped on the grounds of the present-day Haat Bazar for food and shelter.

Photo : Praveen Chettri

Before Young Husband’s Mission to Tibet that catapulted Jelep-la as one of the major trade routes the trade route to Tibet via Jelep-la did exist. However, there were territorial disputes between Tibet and Sikkim. The first police outpost was set up by the first Political Officer to Sikkim, Sir James Claude White at Aritar near Rhenock in 1897. Subsequently, the trade through this route flourished and there was a huge surge in number of traders travelling between Lhasa and Kalimpong. A Dak Bungalow was built in Aritar for traders and administrators alike (mostly used by British traders). Thus, foregrounding the strategic spatial significance of Aritar and Rhenock for the Kingdom of Sikkim.

Photo: Praveen Chettri

Wool, yak tails, silver coins, jaggery, bundles of musk, medicinal herbs, etc. were brought from Lhasa to Kalimpong via Rhenock. However, wool was the most traded item. So much so that people also preferred to call the old silk route the wool route. The items sent from Kalimpong to Lhasa were Indian grains, salt, household implements, cotton garments, and even Rolex watches. These trade exchanges not only facilitated the exchange of goods but also created in the process specialists in trade-related activities. Amongst the trader communities were Tibetans, Newaris, and the Marwaris who dominated the trans-Himalayan trade.

With trade activities, values and the way of life of the traders spread along the way. Trade has made the world a smaller place by connecting distant places – making the international market and all that it has to offer more accessible to not just the trading hubs but also smaller villages along the trade routes.

While Kalimpong was considered to be the major trading hub on the trans-Himalayan trade route, the smaller villages which functioned as halting stations providing a safe passage for the traders too grew with a handful of small-scale businesses emerging in Rhenock, mainly run by the Newari and Marwari businessmen.

Photo : Praveen Chettri

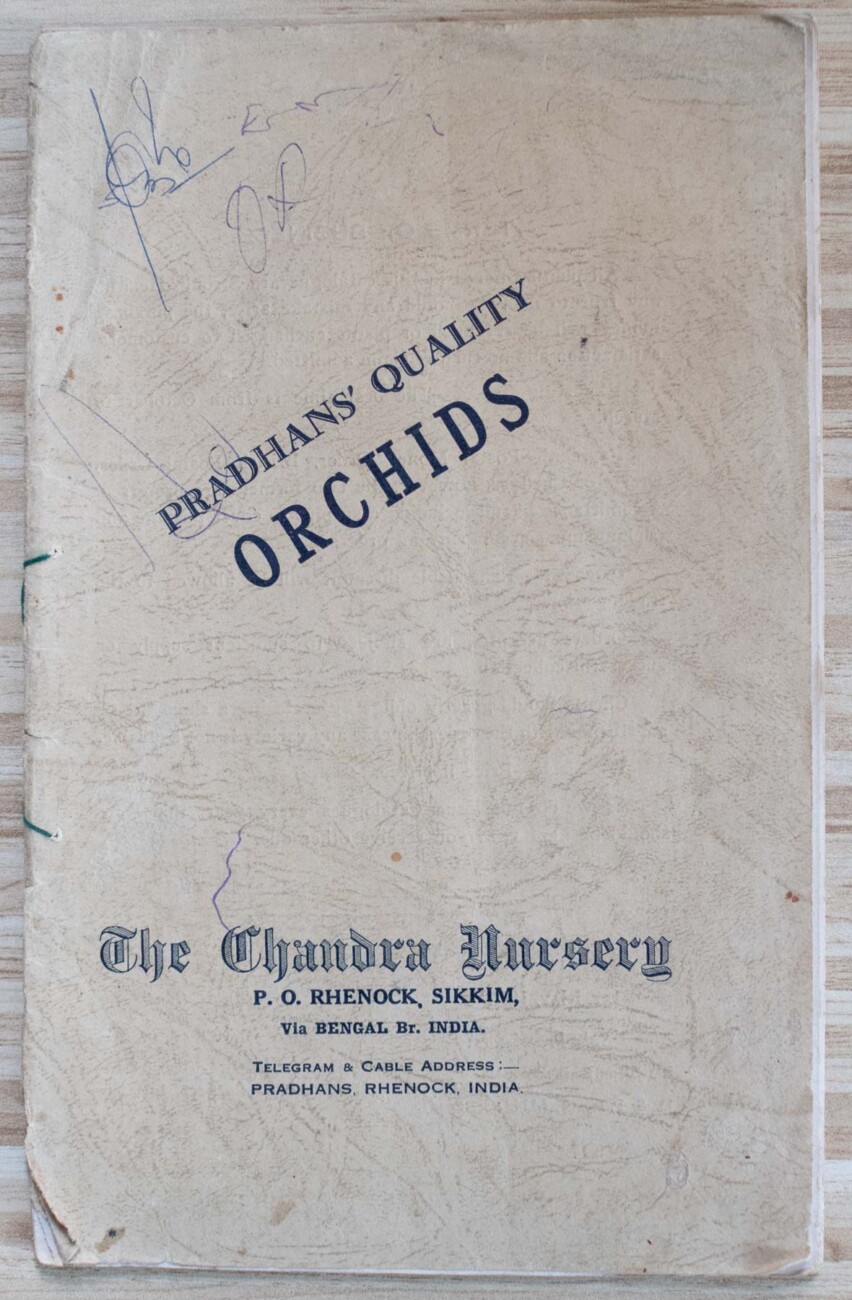

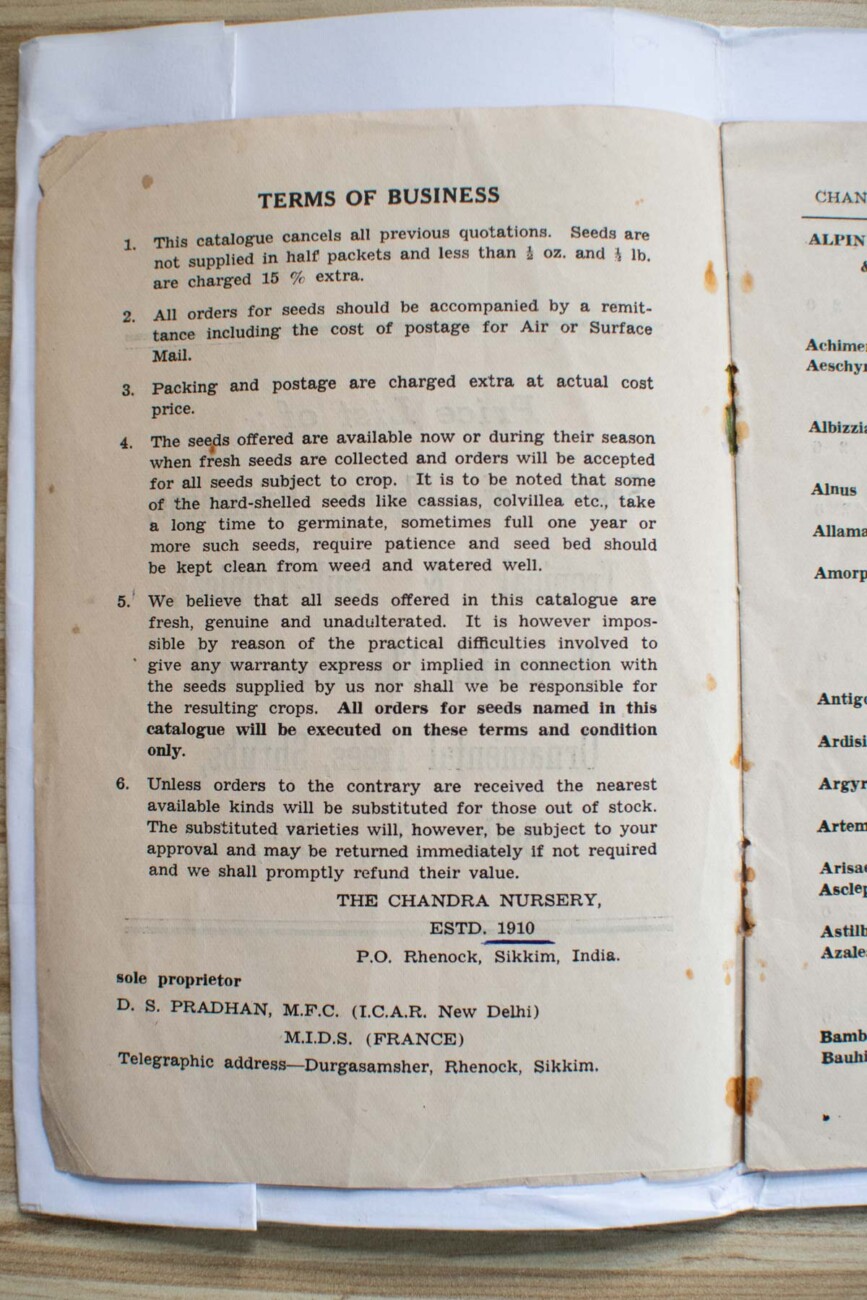

One that made a huge mark in the international floriculture market was Chandra Nursery in Rhenock; started in the year 1910 by Rai Saheb Ratna Bahadur and Rai Saheb Durga Samsher, sons of the famous Taksari Chandravir Newar. He was a land revenue collector and one of the most sought-after Newari businessmen in charge of copper mining in Sikkim among Newari traders like Lakshmidas Pradhan (Kasaju), Chandravir Maske and many others.

The expansion of Chandra Nursery, famous for its variety of Orchids was reinforced by Ratna Bahadur’s excellent rapport as a member of the State Council in Sikkim, with the British Political Officers, Governors and their guests from the United Kingdom who would often visit Sikkim. The flowers at Chandra Nursery especially the Orchids were exported to Britain, the US, Australia, Canada and China.

During one of Ratna Bahadur’s trips to Gnathang he identified a new variety of Cobra Lily that was later named in his honour by Kew Botanist C.E.C Fischer as Arisaema Pradhanii.

The exports, as well as imports of flowers at Chandra Nursery, were facilitated by the services of the Post Office in Rhenock. When cardboard boxes weren’t available for export, alternative containers made of woven bamboo baskets were made to fit the acceptable standard of the postal system – delivering flowers of the highest quality far and wide.

Photo : Stuti Pradhan

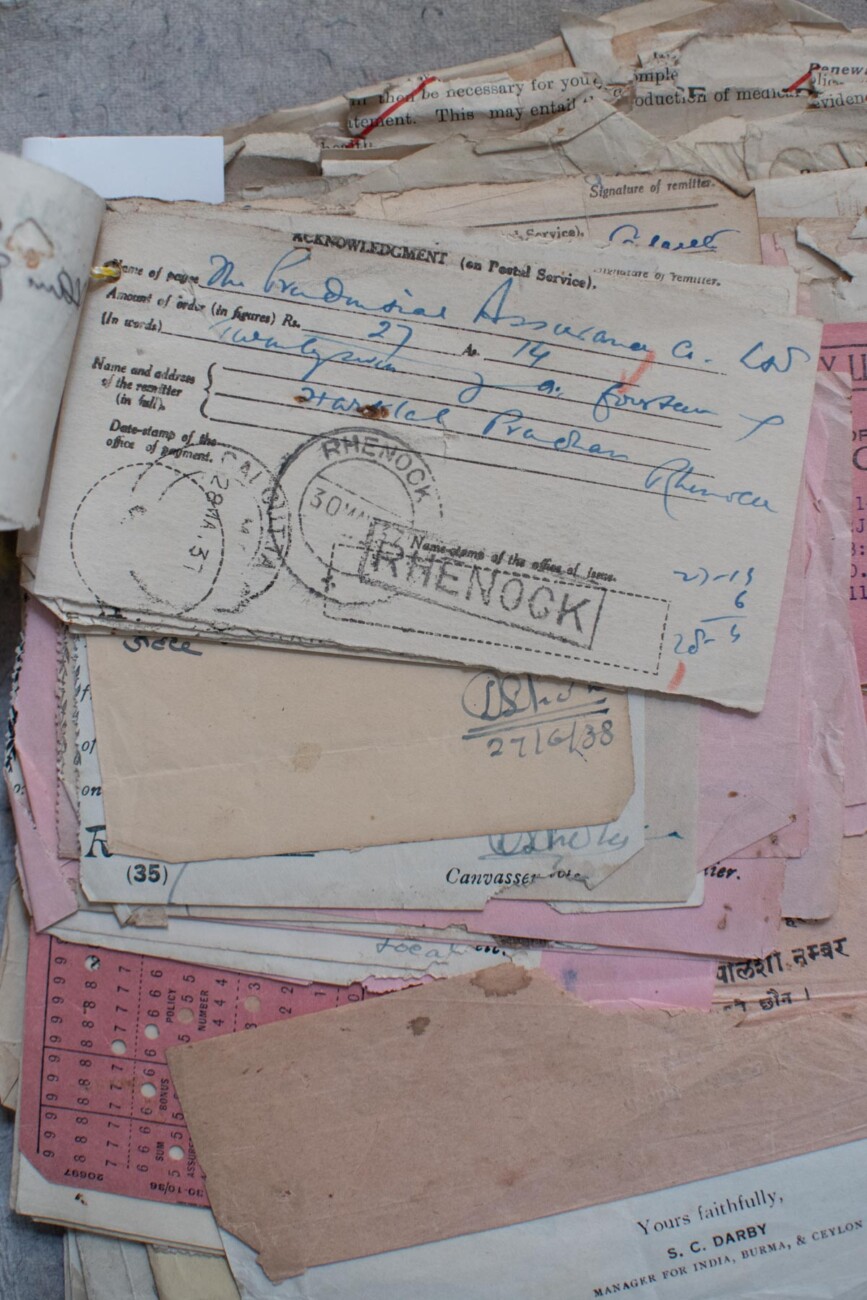

The establishment of the Post Office in Rhenock is also said to be credited to Chandra Nursery for its growing demand for flowers in the international market: ‘P.O Rhenock’ as the Chandra Nursery’s address from the year of its establishment in 1910 – making it one of the oldest post offices to be established in Sikkim.

The establishment of public institutions like postal services in Rhenock marked a shift in terms of including the peripheral societies within the system of the ‘modern world’. These postal services did not just serve as a medium for the exchange of goods but also supported banking facilities/services like housing insurance, credit, etc.

Photo : Praveen Chettri

Social workers like the 98-year-old Shri Sunder Kumar Pradhan, a resident of Rhenock, were among the few who made use of the post office to promote knowledge about medicines and their healing properties by ordering books from Mathura in U.P. and cities in Gujarat through the post office. Recalling his early years, he now laughs at how he almost functioned as a doctor over the years with people still coming to see him for health related queries till a few years back!

A couple of the Rolex watches or other brands found in Kalimpong for export to Lhasa were also purchased by Late Shri Paras Mani Pradhan at the local market in Kalimpong for his Ghari Dokan (watch shop) cum Photo Studio in Rhenock, ushering in the use of modern gadgets in Rhenock.

Photo: Paras Mani Pradhan

Ram Gauri Sangralaya, a nursery and a museum run by Shri Ganesh Kumar Pradhan in Rhenock is one of the many mediums available to us to study the past in order and to understand our present. Following in his father’s footsteps, Shri Ganesh Kumar Pradhan has meticulously archived much of Sikkim’s history. Keeping alive the memories of the many changes that a small place like Sikkim and even smaller towns like Rhenock have witnessed over the last couple of centuries. Ram Gauri Sangralaya is nostalgia in its essence, the longing that helps us understand our present as Carl Sagan (1980) famously stated, “you have to know the past to understand the present.”

Ram Gauri Sangralaya

Photo: Praveen Chettri

Ram Gauri Sangralaya

It is this very nostalgia for the old silk route and Rhenock’s strategic spatial significance that surfaces time and again for people who have witnessed and heard stories of the Lhasa-Kalimpong trade route journeys. This trade route ceased to function soon after the declaration of the Indo-Sino war of 1962. The once-bustling trade route that linked Asia, Europe, and Africa has now become just stories of the past.

Although the people of Rhenock and Aritar, have moved on with their lives, they still hope for the old silk route via Jelep-la to revive through tourism to generate revenue for the locals just as trade did many decades ago. With Rhenock and Aritar’s historic importance still alive in memories and being a witness to the start of public institutions like the post office, police stations, nurseries, and museums along an important Southern Silk Route, it only seems natural for the people to hope for Rhenock’s revival.

Photo: Praveen Chettri

PHOTO GALLERY

(CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Read more about Rhenock

References

1.Continental and Maritime Silk Routes: (2015, January). Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved June 12, 2022, from https://orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/India-China-Cooperation_Report.pdf

2. Harris, T. (2008). Silk Roads and Wool Routes: Contemporary Geographies of Trade Between Lhasa and Kalimpong. India Review, 7:3, 200-222. 10.1080/14736480802261541

3. Kristiansen, K. (n.d.). Theorising Trade and Civilisation. Trade and Civilisation, 1-24. 10.1017/9781108340946.002

4. Majumdar, E. (1994). THE ROUTE : A Study of the Trade Route Connecting the Frontier Trade Part of Kalimpong with the Plains of Bengal and Lhasa (1865-1965). Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 55, 630–638. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44143420

5. Mckay, A. (2012). The British Invasion of Tibet, 1903–04. Inner Asia, 14(1), 5–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24572145

6. Mishra, M. K. (2020). The Silk Road Growing Role of India. Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, 1-30. Retrieved May 21, 2022, from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/216099/1/THE%20SILK%20ROUTE.pdf

7. Sarwar, Lubina. (2017). The Old Silk Road and the New Silk Road: An Analysis of the Changed Discourse.

8. Shresta, R. S. (2010). The Chandra Nursery Centenary (1910 - 2010) - a tribute. http://karunaguthi.weebly.com/uploads/4/6/3/1/4631829/the_chandra_nursery_centenary.pdf

9. Shrestha, B. G. (n.d.). Ritual and Identity in the Diaspora: The Newars in Sikkim. Bulletin of Tibetology, 25-54. http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/bot/pdf/bot_2005_01_03.pdf

Stuti Pradhan has done her MSc in Public Policy from University College London. She’s also a part of Constructing Homelands, a collaborative initiative supported by Khoj International Artists Association, that seeks to engage with migrant women working in the informal sector in Sikkim — further exploring how ethnography and art interventions, especially visual storytelling can together inform a participatory and gender-responsive policy framework.

Stuti is a budding research scholar pursuing PhD in Sociology at Newcastle University, UK. Her research focuses on gender, indigeneity, post-coloniality, and citizenship practices in Sikkim.

I gratefully acknowledge Shri Ganesh Kumar Pradhan who runs Ram Gauri Sangralaya for his unstinting support and encouragment while I was writing this article and for genuinely catering to my curiosity with lovely stories about the history of Rhenock and the Newari traders. Special thanks to Shri Sunder Kumar Pradhan and Anmol Pradhan, his grandson for sharing interesting anecdotes about his early years as a social worker in Rhenock, to Shri Krishna Pradhan, son of Late Shri Paras Mani Pradhan for taking the time to search through their family archives for old photographs. I’m immensely thankful to my parents who helped me get in touch with the resources needed for this article and for their unconditional love and encouragement. Lastly, I’m thankful to Prava Rai and Praveen Da at Project Sikkim without whose support this article wouldn’t have been possible.

4 comments on “RHENOCK: THE FIRST HALTING STATION ON THE SILK ROUTE”

Leave a Reply

Latest Posts

Latest Comments

No 'Comments_Widget_Plus_Widget' widget registered in this installation.

Howdy! Would you mind if I share your blog with my myspace group?

There's a lot of folks that I think would really appreciate your content.

Please let me know. Thanks

I made the same mistake. It's Sir John Claude White, not James. The first British representative of Sikkim.

The article is indeed enlightening and very interesting. It underscores the importance of trade in providing livelihoods to remote communities, and in exchange of modern ideas and goods. The much-maligned Marwari community played a very significant role in Indo-Tibet trade, whether through Kalimpong or through Assam. It is indeed remarkable that a community originating in the hot desert sands of Western India made inroads into Tibet long before others thought that such trade was even feasible. Unfortunately, both Sikkim and Darjeeling District have suffered economically in recent decades because of the embargos placed on the entrepreneurial initiatives of the Marwari. In the whole of Eastern India,they are the only community that has consistently stuck its neck out in maintaining the engines of economic activity running despite a hostile environment in West Bengal, Nepal, Sikkim and perhaps Assam. ( Disclosure: I am not a Marwari by 2000 Km).

Read this with avid interest. Yes Rhenock did play important role in its days.

As a child I remember seeing caravan of mules transporting goods to and from Kalimpong to Yatung and Phari in Tibet. Its true this stopped after 1962 Sino-??Indian War.

I suggest you to go through the book written by K. C. Pradhan. I have read another account by Secretary General of Viceroy, India, who passed this route in 1885 to find pass to Tibet. This book is available. It will give you more details about this area.