The prominent Nepali author M.M. Gurung once penned a collection of stories titled ‘Teesta Bagcha Sadhai Jasto’ (The Teesta Flows as Usual), with stories of everyday life in the Eastern Himalayas woven around the perennial flow of the river. Today, given the unprecedented developmental activities on and in the vicinity of the Teesta River such a title would be inappropriate. With the damming of the Teesta, once considered the lifeline of Sikkim and North Bengal, a more apt appellation would be ‘Teesta Bagdaina Sadhai Jasto’ (The Teesta does not flow like before). It is not the change of its course but the deliberate damming of the Teesta that has brought numerous changes to the ecosystem. After several decades of dam building, new infrastructure projects are still being implemented in the region, the Sevoke-Rangpo Railway project being the latest. This has led to the extinction of several fishes that reproduce and inhabit the Teesta and its tributaries -Rongli, Reshi, Rangpo, Rangeet, Relli, and Riyang. The irresponsible disposal of muck generated by these infrastructural projects flouting all the rules and regulations indicates the authority’s indifference. This article argues that if this indifference is not addressed on time, it will make the Teesta River devoid of any life, gradually leading to its demise. Such a situation will also lead to the erosion of people’s ancient customs associated with the river. Focusing exclusively on the Kalimpong district in North Bengal, this paper considers how the country’s incessant and insatiable drive to develop infrastructure in borderlands while ignoring the impact on the fragile environment is harming the people in whose name development is being implemented.

The entire Teesta basin is an indispensable region in the Indo-Myanmar biodiversity hotspot and these built infrastructure projects are weakening this biodiversity.

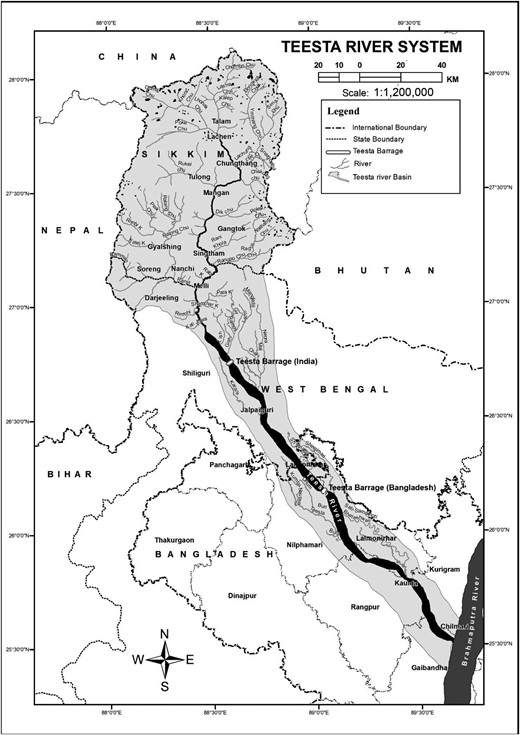

The Teesta originates at an elevation of 23,036 ft. above sea level at Pahunri glacier between India and Tibet. After carving out several picturesque ravines and gorges across the state of Sikkim, it reaches the jurisdiction of the town of Kalimpong where it meets several of its tributaries and distributaries, the prominent ones being- Rangpo, Rangeet, Relli, Rongli, Reshi, and Riyang. The river’s magnanimous ecology and rich fish diversity have now been reduced to an economic resource after an increase in the creation of infrastructure projects in the region. The dams have caused enough havoc and threatened the existence of the entire river ecosystem, now the new Sevoke-Rangpo Railway project is adding to the ordeal. The entire Teesta basin is an indispensable region in the Indo-Myanmar biodiversity hotspot and these built infrastructure projects are weakening this biodiversity. Mr. Shen a well-known authority on the aquatic species of the Teesta River basin says that his grandfather’s generation had seen pink dolphins in the Teesta River. Several locals have also spotted this rare species in the river, and recount it fondly.

“Cultural memory embodied in texts, images, and rituals serves to stabilize and convey that society’s self-image” (Assmann and Czaplicka, 1995: 132). Cultural memories have a greater bias towards the present and they gain greater potency and meaning when performed in public. Middleton and Derek (1990) call such practices as ‘collective remembering,’ while Fentress and Wickman (1992) term it ‘social memory’. It offers vital resources for groups serving as the ‘medium through which identities are constituted’ (Olick and Robbins 1998: 133). The construction of identity vis-a-vis the river is evident in the folklore, festivals, rituals, and stories. Due to the incessant construction activities, the cultural imagination of the people and their attachment to the river is also being affected. The damming of the Teesta River for the generation of hydroelectric power was initiated way back in 1975 when the Government of West Bengal constructed new irrigable land in six northern districts to supply drinking water to Siliguri municipality and generate hydropower at Gajaldoba[1]. Thereafter, a series of barrages and dams have been built on the river, damming most of its catchment area[2]. Currently, in North Bengal and Sikkim, there are about 47 hydropower development projects in different stages[3]. This spate of dam-building activity to harness hydroelectric power for human consumption has led to a severe decline in the aquatic species that inhabit this mountain river.

It all began with the onset of dams on the Teesta River which hampered the migration of fish species. These fishes use the Teesta River as the highway to reach its tributaries for breeding. Before the onset of the monsoon, the migratory fish travel upstream to their breeding grounds. Once the monsoon begins, the water level swells up in the tributaries creating rapids and waterfalls, which act as natural hatcheries for the fish eggs. The locals call this movement Ubauli (April to June,) after the eggs hatch the fry[4] remain in these tributaries, which serve as nurseries for the fry to grow into semi-adults. This is possible because after the monsoon the velocity and depth of the tributaries reduce drastically and the river’s temperature rises slightly, allowing the fry to survive and grow. During Udauli (October to January), the adult fishes travel downstream as the tributaries become too shallow and the waters of the Teesta too cold, so they head downstream to the plains and warmer waters. The imagination of the locals is intrinsically tied to these aquatic organisms. Their movement is keenly observed and their arrival and departure hold significant cultural significance for the people. However, due to the damming of rivers, the migration of these fish species is greatly hindered leading to the extinction of several species which once inhabited the Teesta. When dams began to be constructed, the construction companies were instructed to make fish ladders but they were made without any prior research on the different fish species. Normal ladders have been constructed which are accessible to some fishes, but provide zero accessibility for slow-moving fishes like Goonch (Bagarius Yarrelli)[5], Jalkapoor (Clupisoma Montanum), and catfishes native to the Teesta River. It is because of this locomotory hindrance that both these species are now extinct from this region. Also, the megafauna[6] (with body weight above 50 kilos) have not been able to migrate because the fish ladders are too small to accommodate them. The population of various other fish species is also rapidly declining. The Golden Mahseer (Putitora Tor) an endangered species, also a large cyprinid known to be the toughest freshwater game fish (held in high esteem like the saltwater game fish Tarpon), inhabits the Teesta River basin and its population has been gradually declining with each new dam being commissioned[7]. The Golden Mahseer is a sensitive species that can barely tolerate a modified water environment. This is evident from the decrease in its length recorded over the last century, size composition (predominance of young/ immature individuals), and reduced share in the catch (as low as 5% from 40-50%) from its distribution ranges spread across the Teesta River system.

In 2013 the Teesta III Hydroelectric power project[8] was built, which affected the migration of fish towards Sikkim. Below this dam lies the Relli and Riyang rivers. The Riyang is one of the largest tributaries of the Teesta and the biggest protected breeding ground and nursery for the fish. However, the situation has changed ever since the construction of the Kalijhora dam[9] in 2016.

In 2013 the Teesta III Hydroelectric power project[8] was built, which affected the migration of fish towards Sikkim. Below this dam lies the Relli and Riyang rivers. The Riyang is one of the largest tributaries of the Teesta and the biggest protected breeding ground and nursery for the fish. However, the situation has changed ever since the construction of the Kalijhora dam[9] in 2016. Richard Shen has been working towards the protection of the Teesta River basin and its inhabitants for the last two decades. He is associated with various organizations based out of Kalimpong like ‘Paila’ and ‘Himalayan Anglers Conservation Trust’ (H.A.C.T) a group of conscious locals who practice and teach the ‘catch and release’ method of conservation. They also organize initiatives to clean the rivers, build sustainable businesses on the riverside creating employment opportunities for the locals, and raise awareness about the tragedy happening to the rivers, especially the Riyang. However, they have not been able to ensure the same conservation practices for the Rangeet River as it already has many dams built over it on the Sikkim side, where they cannot intervene legally[10].

The Rangpo-Sevoke Railway[11] project is the last nail in the coffin of the devastated Riyang River.

Photos: Richard Shen

The Rangpo-Sevoke Railway[11] project served as the last nail in the coffin of the devastated Riyang River. There are three points where the constructing agency IRCON[12] (Indian Railway Construction International Limited) is dumping waste into the Riyang River- at Rongchong above Lohapool, then at Rambi, and above the Riyang Bazaar. At these three points, the muck and debris generated from the construction are being disposed of continually into the river without treatment. Furthermore, for this project, 14 tunnels are being built by blasting the mountains which are harming the already fragile landscape. According to Richard Shen, he along with other locals filed a complaint to the ‘West Bengal Pollution Board’ against the complete destruction of the Riyang River. But they have received no response so far. The state authorities' indifference is causing more complexities and worsening the situation. During such situations, where do the people go to save their homes from the onslaught of mega-infrastructure projects? Eventually, one needs to understand who actually benefits from these projects and why the state continues to remain indifferent.

In her research in the wetlands of Turkey, Caterina Scaramelli shows how infrastructures are not just external but produce and exist within more than human ecologies (Scaramelli, 2019). Thus, the creation of infrastructure in the Himalayan region should be understood in the context of increased interaction between humans and other organisms that are a part of their surroundings. Unlike other places, the Himalayas have a complex way of dealing with their environment, marked by various forms of restrictions and taboos, as well as coexistence (De Maaker, 2021). Additionally, the nature of anthropogenic pressure in the Himalayas is also equally complex as one needs to carefully understand the relationship of humans with nature in terms of “their attachment with the land” (Tamang, 2023). In this regard, it is important to understand the idea of Anthropocene[13] which is a rather contested concept today. People’s engagement with nature has transformed the existence of species. Human-induced calamities due to deforestation and interference with the natural course of rivers have already caused a lot of devastation. Chakrabarty (2009) proposes in ‘The Climate of History: Four Theses’ that the advent of anthropogenic climate change spells “the collapse of the age-old humanist distinction between natural history and human history”. Humans are no longer just biological agents they have also become geological agents. The impact of human activities on flora and fauna is so extensive that it has become irreversible. Thus, the attempts by the state to dam the Teesta River, and build roads and railways in a fragile geographical terrain, have wreaked havoc on the natural environment and altered the entire course of life of creatures inhabiting the river. A journey on the NH 10, built along the banks of the Teesta calls for a lament over the state of affairs. For the people in the region, it is the only road connecting Sikkim and Kalimpong to the rest of the country. The frequent and long traffic jams on this route have always been a source of frustration. Recently due to the flash floods, large stretches of the NH 10 at Melli, Geilkhola, and Likhay Bhir got washed away. Due to a rise in the water table by the dams, the water from the Teesta has been seeping under the National Highway 10 for quite some time now. The dams on the river are gradually engulfing the highway.

On the night of 3rd October 2023, the Chungthang dam was washed away due to the “Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF)”, which unleashed complete destruction in the region claiming many lives and damaging property extensively, the aftermath continues to be felt. The dam is a part of the 1,200-megawatt ‘Teesta Stage III Hydro Electric Project and became operational in 2017. It would be wrong to term the tragedy as just natural, rather it is an outcome of a consistent hollowing of mountains (building numerous tunnels to direct water to the dam) in the name of development and growth. The anthropogenic intervention through the creation of mega infrastructure to satiate the needs of India’s growing population is leading to tragic consequences all across the Himalayan region. There have been several protests against the construction of these hydropower projects, which by no stretch of imagination can be termed clean fuel. However, the state and its agencies have tried to depoliticize the people’s resistance through tokenism[14]. Along with the building of dams, other infrastructure projects like the construction of railways are also disturbing the ecological balance of the fragile Himalayan region. The disappearance of aquatic life in the Teesta River, with it drying up at various stretches is a testimony of the destruction. Richard Shen was at the Riyang River for three days (27_ 29 of October, 2023) for a recce to gauge the population of fish after the recent catastrophe. He found that the population has drastically declined - about 80% of the fish have been wiped out. The recent catastrophe at Chungthang on the 4th of October revived memories of the old anglers who said that in 1968 (on the same date interestingly i.e., the 4th of October) a similar catastrophe had occurred, “it took about 10-15 years for the population of the fish species to normalize”. Now with the recent flash flood much larger in scale than the previous one, and an increasing number of dams on the Teesta River nobody knows how much time it will take for the fish population to bounce back or if it will ever happen. Combined with the disposal of debris and muck from the construction of mega infrastructure, the Teesta is rapidly dying. The entire range of fauna, both aquatic and terrestrial are facing the consequences. Thus, one form of infrastructure is being built on the damage done by the other and this vicious cycle knows no stopping. Therefore, it becomes imperative to understand the environmental impact of infrastructure development in the fragile region of the Himalayan borderlands and deconstruct the aspirational development discourse related to it.

Report & Recommendations on GLOF affected areas of Sikkim, Darjeeling and Kalimpong Himalaya, drafted by Save The Hills and Darjeeling Himalaya Initiative

https://savethehills.blogspot.com/2023/11/report-and-recommendations-on-glof.html

| Report & Recommendations.... |

References:

- Anand, N. (2023). Anthroposea: Planning future ecologies in Mumbai’s wetscapes. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758231183439

- Assmann, J., & Czaplicka, J. (1995). Collective Memory and Cultural Identity. New German Critique, No. 65, 125-133

- Chakrabarty, D. (2009). The Climate of History: Four Theses. Critical Inquiry, 35(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1086/596640

- Fentress, J. and C. Wickman. (1992). Social Memory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell

- Maaker, Erik de. (2021). Reworking Culture: Relatedness, Rites, and Resources in Garo Hills, North East India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Olick, J. K., & Robbins, J. (1998). Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practices. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 105–140

- Scaramelli, C. (2019) The delta is dead: Moral ecologies of infrastructure in Turkey. Cultural Anthropology 34(3): 388–416.

- Tamang, S., & Kipgen, N. (2023). ‘Land’ as a site of contestation: Empire, identity, and belonging in the Darjeeling Himalayas. Ethnicities, 23(2), 213-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968221101400

9. https://savethehills.blogspot.com/2023/11/report-and-recommendations-on-glof.html (GLOF Disaster Report, 2023)

[1]It is one of the largest irrigation projects of the north-eastern region of India. Gajoldoba is a village in the Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal.

[2]See the report by Water Council, ‘ Hydropower development along Teesta river basin: opportunities for cooperation’, by Muhammad Mizanur Rahman and Abdullah Al-Mamun: https://iwaponline.com/wp/article/22/4/641/74772/Hydropower-development-along-Teesta-river-basin

[3]See the report by Power Department, Government of Sikkim: https://power.sikkim.gov.in/status-of-ongoing-and or-completed-schemes/

[4] Larval fish live off a yolk sac attached to their bodies. When the yolk sac is fully absorbed, the

young fish are called fry. Young fish are generally considered fry (during their first few months toless than one year in some species).

[5]Popularly known as ‘Limbui Maach’, the Goonch is considered sacred among the Subba community.

[6] Megafauna are important, because bigger the fish, higher the quantity of eggs they reproduce.

[7]See this report by WWF: https://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/priority_species/threatened_species/golden_mahseer/

[8] It is located in Kalimpong district of West Bengal, a little above Rambi Bazaar.

[9] Situated in Kalimpong district, earlier it used to be a popular picnic spot but now it has been submerged by the Teesta III hydroelectric project.

[10]Though divided by state boundaries, Sikkim and Kalimpong-Darjeeling are joined by the tributaries and distributaries of Teesta River and have shared cultural, social, mythological ties and similar predicaments.

[11]The Sevoke-Rangpo Railway Line is currently under construction to connect the Indian states of West Bengal and Sikkim. It branches out from Sevoke town near Siliguri in Darjeeling district and runs through villages and towns of Kalimpong district of West Bengal and terminates in Rangpo, Pakyong district of Sikkim. In the second phase of construction, this line will be extended till Gangtok and later to Nathu La pass, along the border with Tibet. The total length of this railway line is 44.96 kms.

[12] IRCON (International or Indian Railway Construction International Limited) is an engineering and construction corporation, specialized in transport infrastructure. It was established in 1976 by the Indian Railways under the Indian Companies Act 1956. It is the constructing agency for the Rangpo-Sevoke railway project.

[13] Anthropocene, a term coined by American biologist Eugene Stoermer and Dutch geochemist Paul Crutzen, describes a new geological epoch dominated by human activities at all scales, particularly the transformation of the planet’s atmosphere due to fossil-fuel burning.

[14]Recently, “Teesta V Hydropower station at Dikchu, East Sikkim”, received the Blue Planet Prize from the International Hydropower Association, which has been condemned by Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT), an organization which opposed the excessive damming of the Teesta River with warnings of impending disaster.

Archana Pathak is a Ph.D. Candidate at IIT Mandi. Her research interests lie at the intersection of Borderlands, Himalayan studies, and the new anthropology of Infrastructure.

Richard Shen is an authority on the aquatic species of the Teesta River basin and works in tandem with ichthyologists and researchers from all over the country and abroad. He is associated with the H.A.C.T (Himalayan Anglers Conservation Trust), an organisation based in Kalimpong to protect and save native fishes of the Eastern Himalayas.

31 comments on “THE TEESTA NO LONGER FLOWS”

Leave a Reply

Latest Posts

Latest Comments

No 'Comments_Widget_Plus_Widget' widget registered in this installation.

Great article.The river, the mountain and the forest is suffering for development and people greed. Even you can see the construction of buildings going on in Sikkim. It's already cross the threshold level but still we are doing it. Development for what????

Thank you Kenza 👍🏻

Proud of you Richard ...keep up the good work

Thank you Tenzing

Just a week ago I visited Kalimpong. While going from Siliguri to Kalimpong I watched with horror the devastation caused to Teesta, a great river of eastern India. The water is now murky with full of debris and the once green coloured water is nowhere to be seen. Also while traveling from Kalimpong to Darjeeling by Kalimpong - Ghoom road I got the same experience. In the name of development such kind of destruction is a repeated incident in Himalayas, which we regard as the dwelling place of God. If people do not act to stop such destruction of paradise on earth, human race is doomed to perish. When, if not now?

If this is your concern then I suggest you to not visit Darjeeling ever again.

Yes, exploitation in the name of development is an evil.

Very well observed. It all boils down to lack of care from the elected rulers from the plains. If plannings were correctly applied according to the impact assessments then this type of disaster can be avoided. There was a time when rule of law prevailed. But now state government is far too busy in changing the demography in Darjeeling Hills. They implement gradual language annihilation to destroy the culture but cannot look after the place itself. Individuals with pending criminal cases gets the blessing from the government and put at the helm to look after the interest and welfare of the place and its people. If they do not tow the line then the administration would go way beyond legitimate means to make sure what it wants and that happens. Planless structures can be stopped if the administration shows its will. So far Silgadi has been nearly eradicated of its original inhabitants and the trend continues to spread elsewhere. That seems to be the main goal of the rulers.

Excellent article.

I'm a keen angler and I know all the nooks and cranies of these rivers and have fond memories of swimming and angling in them since childhood.

When I see drastic changes in them (dams, quarries, habitations, destructive fishings, etc.,I feel sonetimes like are we in some banana republic!

But against might of money I feel we simply are no match!

I for one surely support Save Teesta, Save Species, Save Nature.

Our natural resources is our treasure trove, we should protect our natural resources for our future generations, the Govt or private individuals will not set up factories or industries in the hills for obvious reasons so the only thing our children can earn from is our natural resources.

Great article!

Kudos to the authors for talking about the important environmental problems around the Teesta River and the ongoing building projects in the Himalayan region. This article really helps us understand how development, harm to the environment, and preserving our cultural history are all connected. It's an important read that highlights the need for careful and eco-friendly practices in the Himalayan areas.

Good job! Proud of You Archana Pathak.

Thank you Sir.

Yes , nature has its own bounty but extinguishable. If the human race wants to survive and thrive then we need to protect these resources also. Water is an integral part in the human race survival , if we neglect this , we are doomed and there is no turning back, let’s not burn our bridges behind! These kind of articles are eye openers , let’s not ignore. A well researched and put forward words of wisdom!👍

Thank you Ma'am.

Genuine concerns brought to light, and very rightly mentioned that Hydro power doesn’t seem to be as clean as it is perceived to be. A right balance between development and ecology needs needs to be struck.

A balance totally agree.

Teesta Must Survive & live on.

Yes Rishi, we all should advocate for our natural resources.

As a Sikkimese reader, I'm thankful to the author for dedicating time to research and advocate for the Teesta River's ecology and survival. The article strongly highlights the impact of damming and two decades of waste disposal on the river.

It's more than just information; it's a heartfelt plea to safeguard the essence of the Teesta. Kudos to the author for being a voice for Sikkim and prompting us all to pay attention and take action.

Thank you so much for your kind words.

This is so educational - and everyone has to read it and understand that development is not the only answer we need! The destruction that we are all witnessing has to be taken seriously by everyone... The fishes are going... We'll be gone too at this pace!

The destruction of Teesta needs to be taken very seriously, indeed.

In Eden's garden, creation's breath, God's canvas painted, untouched by death. Nature's symphony, a perfect rhyme, A world in harmony, a sacred time.Yet echoes of disobedience cast a shadow, Human hands sculpted both joy and sorrow. Paradise marred by choices unwise, Man, in hubris, sought a different prize.Rivers tainted, skies obscured, In nature's course, disruptions endured. Forests weep for what once was pure, As mankind's touch takes its toll for sure.Yet hope remains in the gentle breeze, Redemption whispered through ancient trees. In stewardship, a chance to restore, The beauty God crafted forevermore.

.... Twin

Beautifully summarised, thank you.

Good information and intresting research. Keep it up.

Good luck.

Thanks a lot.

Great work brother. I wish the concerned departments/authorities look into this matter seriously. Sad to see that conservation and safeguard of planet in all manners are merely a topic in school syllabi.Thank you both for taking this initiative.

Thank you 👍🏻

Well written and very true... Locals don't benefit much from these mega infrastructure development but end up paying a huge price for it....what happened on 4th of October was more of man made than Nature related.National Highway toward Sikkim runs along river Teesta, so from security point of view.. It's not wise to dam river Teesta as water can be used as a weapon and 4th October 2023 incident clearly shows all China needs to do is bomb some lakes situated in the higher himalayan region and the life line of sikkim NH 10 could be easily disrupted and Sikkim cut off from India.

Absolutely in agreement

Teesta has to flow free always.

Proud of you brother Richard sen